On this page:

Introduction

This guide aims to provide library and knowledge services staff with an overview of artificial intelligence (AI) along with practical advice in areas such as copyright, ethics and information literacy.

It also serves as a resource for staff to assist users of library services. While not offering expert AI advice, it focuses on recommendations in the library and knowledge services context.

This guide was created in partnership with library professionals working in NHS Scotland.

As AI is rapidly evolving, this guidance will be regularly reviewed and updated to ensure its accuracy and relevance.

What is artificial intelligence?

Artificial Intelligence (AI) is the use of computer systems to perform tasks that usually require human intelligence. These tasks involve:

- learning (acquiring information and rules for using the information)

- reasoning (using these rules to form conclusions)

- self-correction (adjusting these rules in response to mistakes).

Common examples of AI use include chatbots, facial recognition, predictive text, product recommendations, speech and image recognition, spell checks, translators, virtual assistants, and virus checkers.

AI has the potential to offer significant benefits to the health and social care sector. Some examples where AI could help include, decision support, data analysis, telemedicine, and streamlining of administrative tasks.

There are also potential risks in using AI, such as ethical issues, misinformation, and copyright implications, which will be covered in more detail in this guide.

What is generative AI?

Generative AI is a type of artificial intelligence that creates new content, based on data the system is trained on and messages or prompts they receive.

Generative AI can be used to create images, videos, code, and presentations; summarise information; generate text for emails, papers, and other forms of communication; and engage in conversations with users.

Large-language models (LLMs) are a key component of generative AI, allowing tools to generate text that reads as if it were written by a person.

Examples of Generative AI tools:

- ChatGPT – one of the most familiar examples of a large language model is ChatGPT

- Gemini, (formerly known as Bard), is a Generative AI tool developed by Google. Gemini

- Copilot – this Generative AI tool is integrated into Microsoft 365. A version of Microsoft Copilot, called Copilot chat is available to NHS Scotland staff through their work account. Microsoft Copilot

- AI image generators include DeepAI and Dall-E 3. Other tools such as Canva and Padlet have image generation features.

What does your organisation say about the use of generative AI in the workplace?

Generative AI is an emerging technology and there may be risks in using these tools in a workplace setting. As a result, some NHS Scotland Boards are currently restricting or preventing access to tools such as ChatGPT.

Before using any generative AI tool, you should refer to your organisation’s policy on acceptable use, if available, or contact your Information Governance team if you are unsure.

Generative AI must not be used for clinical decision-making or direct patient care. These tools are not substitutes for professional judgment or regulated systems. In the guidance on Getting Started for Copliot chat, it states "Copilot Chat at NHS Scotland should not be used for clinical decision-making, diagnostics, or as a substitute for a healthcare professional's expertise. It is not intended to support clinical care and cannot be relied upon to inform treatment decisions, determine patient care pathways, or interpret clinical data." (Microsoft, 2025)

Copyright and licensing implications

There was a government consultation on copyright and AI between December 2024 and February 2025 (Crown Copyright, 2024). The government has repeatedly hinted that it wants the UK to be flexible around the implementation of AI, but what this means and how that affects your position as a user has not yet been codified in law. Copyright is enshrined in law and therefore it is important to understand how that affects generative AI.

AI and copyright in UK law:

The law currently in force in the UK makes no specific mention of AI in relation to copyright, however, we need to apply the law as it stands, while the UK government consults with stakeholders on AI and the law.

Some academic publishers are considering introducing contract clauses or additional licences that define what subscribers can do with the content they pay to access, including restrictions on analysing subscription material using AI technology. The Copyright Licencing Agency (CLA), who distribute payment to authors and publishers for the use of their copyrighted content via a licencing scheme are also consulting with licence holders. The CLA have developed a set of principles to help ensure that generative AI is developed safely, ethically and legally (Copyright Licensing Agency, 2024). However, in a developing area, it is in the interests of subscribers to ensure that new licences do not override or undermine the existing fair dealing exceptions in UK law.

Exceptions, text and data mining and fair dealing: interpreting the law as it stands

Text and data mining is the process of using computational analysis to extract information from large datasets, often for research purposes.

- The text and data mining exception in UK copyright law, section 29a of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 (UK Government, 1988), refers to "computational analysis" and allows you to make entire mechanical copies of copyrighted work for the purposes of text and data mining, for research, for non-commercial purposes, provided there is legal access to the material being copied e.g. via a licensed subscription.

- Using an AI programme or platform for computational analysis, for non-commercial research, is permissible under exception 29a., as long as the data is not shared outside our organisation.

What about AI platforms learning from the work we analyse?

- The exception for non-commercial research does not apply to copies made by commercial AI platforms which train their AI systems.

- When using an AI platform, we need to ensure that the platform being used holds the data being analysed in what is call a “walled garden” a secure environment where data is held and not shared more widely or used for AI training. Read the terms and conditions of any tool you want to use for this purpose carefully.

- We have no assurances about what happens to the information we give to AI platforms including Copilot chat, and other commercial AI platforms, e.g. ChatGPT or Google Gemini, so do not upload copyrighted material, such as licensed full-text journal articles, to these platforms unless expressly permitted or if you have a specific licence for their use. Although Microsoft Copilot is protected by Enterprise Data Protection (EDP) under the NHS Scotland license, in the absence of clarity from UK law, Scottish government or internal governance across NHS Scotland our advice is not to upload licensed full-text journal articles into Copilot chat. This advice will be reviewed and updated as the official position becomes clearer.

What about the copyright of text or images we create using AI platforms?

- UK law protects the copyright of works created using human creative choices, so generative AI outputs with a significant human input would be protected currently e.g. if we take a copyrighted image, created by a human and alter this, the copyright still belongs to the original creator, unless they have applied a licence allowing people to make modifications.

- Entirely machine created works are not currently protected.

Ethics on the use of Generative AI

The UK Government has released guidance on the safe, effective and responsible use of AI (Department of Science, Innovation and Technology, 2025). It states ten key principles that form the foundation for the ethical use of AI, which could also be applied to generative AI. When you adhere to these ten principles you are on your way to being a responsible user of generative AI.

The ten principles are:

- You know what AI is and what its limitations are

- You use AI lawfully, ethically and responsibly

- You know how to use AI securely

- You have meaningful human control at the right stage

- You understand how to manage the AI lifecycle

- You use the right tool for the job

- You are open and collaborative

- You work with commercial colleagues from the start

- You have the skills and expertise that you need to build and use AI

- You use these principles alongside your organisation’s policies and have the right assurance in place.

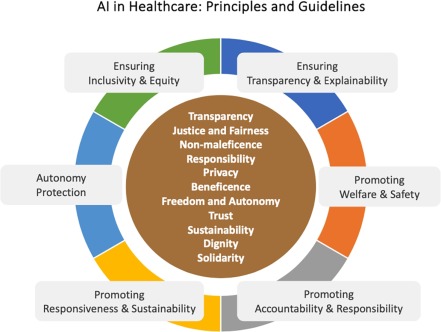

The World Health Organisation has also provided a set of key ethical principles and guidelines on the use of AI in healthcare (World Health Organisation, 2021).

- Protecting human autonomy

- Promoting human well-being and safety and the public interest

- Ensuring transparency, explainability and intelligibility

- Fostering responsibility and accountability

- Ensuring inclusiveness and equity

- Promoting AI that is responsive and sustainable.

Figure 1: Ethical principles and guidelines (Mannella et al., 2024)

What is the ethical challenge with generative AI?

Always keep in mind that the ‘next step’ is based on an artificial entity with no roots in reality. We as humans have the ability to ‘weigh’ decisions on experience and observation, although efforts are made to introduce this in large language and image models, it is nearly impossible to replicate to the point where no mistakes are made.

Generative AI programmes ‘learn’ in a variety of ways. At the foundation they utilise large data sets that have been curated with a view to help an algorithm develop a rudimentary understanding of linguistic rules. But the programmes also learn through so called ‘human feedback loops’. If you have ever used ChatGPT or Gemini, you will know that it encourages you to give a ‘thumbs up’ or a ‘thumbs down’ and provide written feedback. This interaction with the system ‘teaches’ the (future) system what is right and wrong. Another element is that in some forms of generative AI, your ‘prompt’ teaches the system, the way you phrase it, but also the content you provide. For example, if your question is:

“Which non-analgesic painkillers could I use for a patient with chronic backache?”

The system may well decide that ‘non-analgesic painkillers’ are an actual thing. If enough people ask about ‘non-analgesic painkillers’ the system learns that this concept is real. Despite it being a misunderstanding which should state ‘non-opioid analgesic painkillers’.

You should adhere to this basic rule for using Generative AI: Never assume that the text, or image, generated is accurate or reliable.

Some other relevant issues to be aware of:

Data protection (GDPR) and Caldicott still apply

Although AI is a relatively new phenomenon, information systems are not and the same principles, for example the Data Protection Act 2018 and Caldicott still apply. You should never input information that is classified or sensitive into any of these tools as there is a real and acknowledged risk that this data becomes ‘absorbed’ into the data-set of the large language model.

Tests on early large language models have demonstrated that it was possible to retrieve personal data related to specific individuals, including those that were not of public interest. Most large language models also log all prompts and these logs are ‘human readable’ as they are used for verification of models.

Ethical concerns around computing power and environmental impact

It isn’t always obvious to us, as end-users, how large and complex the systems we use are and what their impact on the environment is. The Verge reported that the processing power required to power large language models has pushed overall electricity use for the internet to a whole new level. Whereas advances in efficiency of processors had stabilised the growth of energy demand of the internet, it is now estimated that the total energy use of data-centres, so including AI activity, may well double total demand by 2027. At that point the internet would require the same total electric input as Germany (Vincent, 2024).

Other environmental concerns include water consumption, greenhouse gas emissions and the manufacturing, transportation and disposal of AI hardware.

Writing for publication

If you are preparing work for publication, it is important to check the publisher’s guidelines on how to disclose and document the use of artificial intelligence. Many publishers now require authors to explain how AI tools were used during the writing or research process. For example the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE, 2025) provides helpful guidance on acknowledging AI-assisted technologies in scholarly work. Being transparent about AI use helps maintain trust, integrity, and clarity in academic and professional publishing.

Referencing the generative AI tool you have used

If you are using generative AI in your work, it is good practice to either acknowledge it or cite it formally.

It can be very tempting to ‘quickly draft’ a text and share that as your own work, but the receiver of that text should be aware that they are in fact reading the output of a generative AI tool so that they can assess the content in an appropriate manner. When using generative AI tools ensure that you include a statement to that effect.

It is up to the author of a text to decide what statement they wish to include, but general advice is to include:

- the specific large language model used (for example Microsoft Copilot)

- the date(s) that the large language model was consulted (for example June 2025)

- a statement that all output was verified by the author before being included.

Example 1

Microsoft Copilot was used to assist with the initial drafting of this document. The author reviewed and verified all AI-generated content before inclusion. Accessed June 2025.

Example 2

Microsoft Copilot was used to draft an all staff email, a short news article, and sample social media statements to support the development of a communication plan promoting the launch of a new e-learning module. All AI-generated content was reviewed, edited, and approved by the author before circulation. Accessed November 2025.

When quoting or paraphrasing AI-generated content, use a formal citation style. Below are examples in Harvard or Vancouver formats:

Harvard style

- In-text citation: (Microsoft, 2025)

- Reference list: Microsoft (2025) Copilot. Available at: https://copilot.microsoft.com (Accessed: 15 June 2025)

Vancouver style

- In-text citation: [1]

- Reference list: 1. Microsoft. Copilot [Internet]. 2025 [cited 2025 Jun 15]. Available from: https://copilot.microsoft.com

There are specific frameworks in development for situations where generative AI was used in research, for example TRIPOD-LLM Statement (TRIPOD, 2025). And when utilising AI in research it becomes even more important to acknowledge the use of these resources.

Other useful sources when using generative AI in research include:

- Generative Artificial intelligence tools in MEdical Research (GAMER) checklist. A reporting guideline for generative AI use in medical research, covering declarations, tool specifications, prompting techniques, and verification standards. This reference contains the latest guidance on citing AI in medicine, complete with examples from real publications. (Luo et al., 2025)

- JAMA network guidance. Offers editorial policies for authors, peer reviewers, and editors on the responsible use of AI tools. (Flanagin et al., 2024)

- UKRIO guidance. Suggests that you follow the guidance from your "field or discipline." (UK Research Integrity Office, 2025).

Policy and frameworks

Given that we are still at the start of a long journey in the use of AI within healthcare, it is vital organisations assess the trust and risk factors for AI tools appropriately, utilising the established Information Governance policies. When considering whether to utilise an AI based product in the organisation, ask yourself these questions:

- What do we use AI for?

- What do we not use AI for?

- What systems have been agreed for use?

- What systems have not been agreed for use?

- What are the basic principles that guide our use of AI?

- How will our existing patient safety, privacy standards, data control and existing regulations fit in with new AI use? Do any of the controls and systems contradict one another?

- How much control will your chosen AI system have?

- What safeguarding systems are in place around use of AI for patient care?

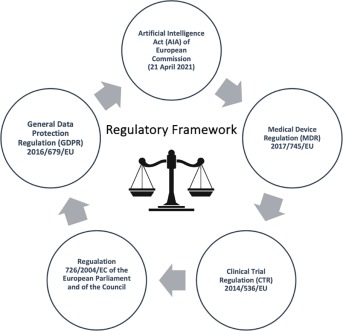

The following diagram shows the various regulatory frameworks that are used for the management of AI and other ethical use of online data. Each framework needs to be considered in the use of AI and/or App use.

Figure 2: Evidencing key European acts to govern AI in healthcare (Mannella et al., 2024)

The Scottish Government is working with the Information Commissioner’s Office (ICO) and the AI Alliance Scotland to provide guidance and advice for Information Governance professionals.

Artificial intelligence and information literacy

It is important to keep the many limitations of generative AI in mind while using these tools. Although many use Large Language Models such as ChatGPT or Gemini as a tool to find answers, they are in fact not always suitable or reliable. For example:

- The AI model may not have access to all the data required to fully answer a question, paywalled content such as The Knowledge Network subscriptions are generally not included. The Knowledge Network

- It is possible that outputs may be biased if the data used to train the AI model was lacking in diversity. The answer you receive may not accurately reflect the population you are working with in the health and social care sector in Scotland. There is also the possibility that an algorithm could have been developed in a way that perpetuates bias, for example by using data that reflects stigma or disadvantage.

- Generative AI tools lack understanding of the real world, they cannot appreciate contextual factors or add nuance which is key in health and social care.

- It is important to be mindful of information governance standards; confidential and copyrighted information should not be shared with generative AI as it may be absorbed for a new learning cycle as content.

To mitigate these limitations, it is essential to "keep the human in the loop" (CILIP, 2021) to carry out the complex task of interpreting, validating and refining AI-generated results to carefully check outputs for accuracy, clarity, sense and meaning.

Library staff can serve as bridges or translators (knowledge brokers) within their organisation regarding AI (CILIP, 2021). They bring “critical thinking, emotional intelligence, and domain expertise that cannot be fully replicated by AI” (Lund, Khan and Yuvaraj, 2024). Library staff are encouraged to adapt by translating existing skills such as critical appraisal and developing new ones such as prompt engineering, the process of designing and refining prompts to effectively interact with AI models, such as generative AI tools (CILIP, 2021).

While not AI experts, there is an important role for local health libraries in ensuring that NHS Scotland staff are well-informed of generative AI's potential and pitfalls.

Find out more

The Scottish AI Alliance, a partnership between The Data Lab and The Scottish Government have developed a free, beginner-friendly course, covering basic AI concepts, real-world applications, ethical questions and the social impact of AI, including modules covering AI and healthcare and AI in the public sector.

Developed by NHS Education for Scotland on behalf of Scottish Government and COSLA, the artificial intelligence pathways offer learning resources and reflective activities to help broaden your knowledge of AI in health and social care.

Artificial Intelligence (AI) Pathway Turas Learn

The M365 skills hub provides useful guidance on using copilot chat, including guidance on writing effective prompts.

Copilot chat guided learning modules

The CILIP AI Hub hosts research, videos, papers and case studies on AI in knowledge, information management and libraries. CILIP is the library and information association.

Access help with searching for the right information to meet your needs by visiting the information skills pages on The Knowledge Network or contacting your local library service.

Information skills pages on The Knowledge Network

Contact your local library service

NHS Lanarkshire library services produce a quarterly current awareness bulletin on the topic of artificial intelligence and its’ uses in healthcare.

Access the AI and healthcare current awareness bulletins

If you are a medicines information professional or working in medicines advice services, the UK Medicines Information (UKMi) network have produced a position statement on the use of artificial intelligence.

UKMi have also produced a second position statement for all NHS staff who provide medicines advice or answer medicine related questions. Alongside this, they have created an infographic that explains key points about using artificial intelligence when handling medicines related queries.

This is available from their recommended resources and tools page.

Glossary of key terms

Artificial Intelligence (AI): The use of computer systems to perform tasks that usually require human intelligence, such as learning, reasoning, and self-correction.

Attribution: The ability for an LLM to cite where the information came from in their generated response. Not all Gen AI companies track where data comes from.

Generative AI: A type of AI that creates new content based on data the system is trained on and messages or prompts it receives.

Hallucinations: Wrong responses from the LLM which happen more often when the LLM is missing information, has incorrect information or information disputed in its training.

Human feedback loops: The process by which AI systems learn from user interactions, such as thumbs up or thumbs down feedback.

Human in the loop: A model of AI system design that involves human oversight and intervention to ensure the accuracy and reliability of AI outputs.

Large Language Models (LLMs): AI models that use large datasets to develop an understanding of linguistic rules and generate text.

Machine Learning (ML): Sometimes considered as a type of AI, but it does not generate information. ML uses historical data to identify patterns to identify that pattern in new data it is exposed to.

Prompt engineering: The process of designing and refining prompts to effectively interact with AI models, such as generative AI tools. It involves crafting specific inputs or questions to guide the AI in generating desired outputs, ensuring the responses are accurate, relevant, and useful. Prompt engineering is a critical skill for optimising the performance of AI systems and obtaining high-quality results.

Text and data mining: The process of using computational analysis to extract information from large datasets, often for research purposes.

Walled garden: A secure environment where data is held and not shared more widely or used for AI training.

References

Cited references

CILIP (2021) The impact of AI, machine learning, automation and robotics on the information professions: A report for CILIP. (Accessed 25 February 2025)

Copyright Licensing Agency (2024) Principles for Copyright and Generative AI. (Accessed 16 April 2025)

Crown Copyright (2024) Copyright and AI: Consultation. (Accessed 16 April 2025)

Department of Science, Innovation and Technology (2025) Artificial Intelligence Playbook for the UK Government. (Accessed 16 April 2025)

Flanagin, A., et al (2024) 'Reporting Use of AI in Research and Scholarly Publication—JAMA Network Guidance' JAMA, 331(13), pp.1096-1098. (Accessed 29 October 2025)

International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (2025) Defining the Role of Authors and Contributors. (Accessed 10 October 2025)

Lund, B.D., Khan, D. and Yuvaraj, M. (2024) ‘ChatGPT in Medical Libraries, Possibilities and Future Directions: An Integrative Review’ Health Information & Libraries Journal, 41(1), pp.4-15. (Accessed 25 February 2025)

Luo, X., et al (2025) 'Reporting guideline for the use of Generative Artificial intelligence tools in MEdical Research: the GAMER Statement' To be published in BMJ Evidence-Based Medicine. (Accessed 29 October 2025)

Mannella, C., et al (2024) 'Ethical and regulatory challenges of AI technologies in healthcare: A narrative review’ Helyion, 10(4), pp. e26297. (Accessed 14 March 2025)

Microsoft (2025) Microsoft-delivered training for Copilot Chat - June 2025. (Accessed 10 November 2025)

TRIPOD Statement. (2025) TRIPOD-LLM: Reporting guideline for studies using large language models. (Accessed: 5 May 2025)

UK Government (1988) Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

(Accessed 14 March 2025)

UK Research Integrity Office (2025) Embracing AI with integrity: a practical guide for researchers. (Accessed 29 October 2025)

Vincent, J. (2024) How much electricity does AI consume? (Accessed 14 March 2025)

World Health Organisation (2021) Ethics and governance of artificial intelligence for health: WHO guidance. (Accessed 2nd May 2025)

Additional references consulted

Department of Health (1997) The Caldicott Committee: Report on the review of patient-identifiable information. (Accessed 5 May 2025)

Dijkstra, P. et al. (2025) ‘How to read a paper involving artificial intelligence (AI)’, BMJ medicine, 4(1), pp. e001394-. (Accessed 20 May 2025)

Headdon, T. (2023) The text and data mining copyright exception in the UK “for the sole purpose of research for a non-commercial purpose”: what does it cover? (Accessed 18 February 2025)

Johnson, A. (2024) ‘Generative AI, UK Copyright and Open Licences: considerations for UK HEI copyright advice services [version 1; peer review: awaiting peer review]’, F1000 research, 13, pp. 134–134. (Accessed 14 March 2025)

Lacey Bryant, S., et al. (2022) 'NHS Knowledge and Library Services in England in the Digital Age' Health Information & Libraries Journal, 39(4), pp.385-391. (Accessed 25 February 2025)

KnowledgeRights21 (2024) Undermining scientific research: why are legacy publishers trying to prevent universities from undertaking AI? (Accessed 18 February 2025)

Scottish Government. (2021) Scotland's AI Strategy: Trustworthy, Ethical and Inclusive. (Accessed: 5 May 2025)

UK Government (2018) Data Protection Act 2018. (Accessed 5 May 2025)

Date updated: November 2025

Review date: February 2026